Jacques Morali: Disco's Visionary Producer

From the Village People to "Brazil," He Connected France and American Disco Scenes

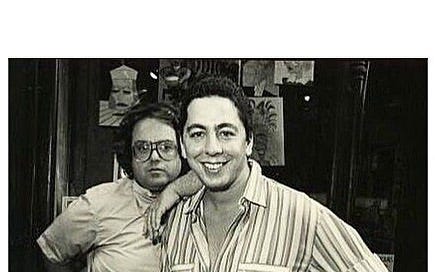

Jacques Morali (July 4, 1947 – November 15, 1991) was a Moroccan-born French singer, songwriter, and producer who was likely one of the most important European producers of disco (in addition to Giorgio Moroder, of course). He’s likely best known as the creator of the Village People. Born in Casablanca and then raised in France, Morali began his music career in Paris before massive success in the U.S. disco scene.

Blending catchy tunes with bold visual concepts, he co-wrote hits for Eartha Kitt, Cher, and Patrick Juvet, among many others. Morali’s work became synonymous with disco, developing entirely new styles and connecting French and American pop scenes. As a gay man, he was made a pariah in the music scene after the 1970s before succumbing to AIDS-related complications in 1991 at the age of 44 - but he left a legacy of music that celebrated joy - and resilience.

Morali’s inspiration for the Village People came during a night out at Les Mouches, a popular gay club in Greenwich Village, New York City. Seeing men dressed as "macho male stereotypes" at a costume ball sparked the idea to form a group of singers and dancers, each embodying a different gay fantasy figure. The result was the Village People—an act known for disco anthems well outside of the normal limits of the genre. Essentially a boy band (a “man band”?), the Village People had massive success with hits like “In the Navy,” “Y.M.C.A.” and “Macho Man.”

It’s almost impossible to say how many times YMCA has been played, but it’s often featured at sporting events internationally - not known for being the most open and tolerant of venues. Whatever your opinion about the band, The Village People were decades ahead - and yet right on time - of American culture.

Morali’s Disco Evolution

Morali’s American disco journey began in 1975 with a remake of Ary Barroso’s “Aquarela do Brasil.” The Ritchie Family version, just titled “Brazil,” blended samba's rhythms and disco beats to become one of many, many disco remakes of songs from other genres to create a track that was peak 1970s disco.

After "Brazil," The Ritchie Family continued made other concept albums like "Arabian Nights" (1976), with tracks inspired by Middle Eastern music and stories, and "African Queens" (1977), celebrating iconic African figures through disco. Both are worth a listen.

Barroso’s “Brazil” inspired many covers across genres and lent its name to Terry Gilliam’s 1985 dystopian movie Brazil, depicting a surreal, Orwellian society—a stark contrast to Morali’s vibrant disco escapism.

For a wonderful version of the original "Brazil"—take a listen.

In 1978, Morali created a disco homage to the U.S. with Swiss singer Patrick Juvet: “I Love America.” It became a European and American dancefloor hit for a moment, reaching #12 on the UK Singles Chart and #5 on the U.S. Billboard Disco chart.

The Duality of Disco

Morali’s work used disco to connect Europe and America, to reconcile optimism and reality, to create joy in the midst of sadness while bringing LGBTQ+ culture into mainstream awareness. I think we all knew the Village People were meant to be gay and it was good and fun for kids to sing along with - I can’t think of a single wedding I’ve been to where the song wasn’t played.

Beneath the glittering exterior of his music were harsh realities faced by many gay men in America, including persecution, social exclusion, governmental neglect, and the utter devastation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, purposefully ignored at the time as a pandemic raged through America.

Despite its widespread popularity, disco faced serious backlash, pretty much epitomized by the infamous Disco Demolition Night on July 12, 1979. It was a chaotic event held at the Chicago's Black Socks baseball stadium, Comiskey Park. It devolved into a riot where nearly 50,000 people gathered as 20,000 disco records were destroyed in a bonfire on the baseball field. People stormed the field and carnage ensued.

This anti-disco stunt, fueled by disdain for the genre’s commercial dominance and cultural influence, exposed deep-seated homophobia and racism targeting disco’s strong ties to LGBTQ+, Black and Latino communities. Unlike the many events that many people had felt privately or in individual and personal violence, this was broadcast on live TV.

Disco Legacy

When disco was declared “dead” later in 1979, Morali’s success waned. He became bitter and reclusive, avoiding similar night life scenes that he used to thrive within. After being diagnosed with HIV, he chose to marry his lover’s mother to make sure that his estate would not pass to his own mother. I rarely hear Morali's name mentioned, but every single person I know can start singing YMCA off the top of their head.

There is still hope and escapism in his work, even with the painful realities he and others faced in the LGBTQ+ community.

It's hard not to see echoes of that today; the country you woke up in remains the same one you fell asleep in.

And yet, disco endures—one of the greatest musical art forms ever created, reminding us of joy, of liberation, and of resilience in the face of a terrible history.

In France today, disco is experiencing a real resurgence, as many young artists embrace and reinvent the genre for today. I’ll be exploring some of that in the coming weeks, even though I love the classics.

Lastly, if you need a little French music, or just a giggle, here’s a French karaoke version of YMCA. It’s not that good, but it is fun.

Try to sing along.