Shrimp, Grits, and the French Connection: A Transatlantic Culinary History

How a Southern Staple Reflects Centuries of French, Indigenous, and African Influence

Long before shrimp and grits became a Southern classic, its core ingredients—corn and seafood—had already been shaping culinary traditions across continents. From the Timucua and Apalachee in Florida to the Huguenots of La Rochelle, Saintonge, and Poitou, and from West African maize dishes to French country cooking, this humble dish is a reminder of the deep historical ties between Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

Shrimp and Grits: A French Take on a Southern Classic

I’m in Jacksonville, Florida this week—a city with some surprising French connections. Not only was it one of the first sites of European colonization in North America, it’s also officially twinned with Nantes, France, where I live. Which, as far as I can tell, means there’s a plaque somewhere in town (and maybe the occasional cultural exchange).

I know shrimp and grits as Southern cooking or Soul Food, both close translations of cuisine paysanne or cucina povera into American English. While I use "Southern" and "Soul" interchangeably, there are some real distinctions that someone better qualified could tell you. But as I know it:

Southern food is a broad regional cuisine rooted in European, Indigenous, and African influences, while Soul Food is a distinctly Black American culinary tradition, emphasizing resourceful, deeply flavorful dishes that originated in the kitchens of enslaved and emancipated African Americans.

What truly defines American food is adaptation—people bringing their culinary knowledge to new places.

For a deeper dive into the history, especially of Black American cuisine, The Jemima Code is a great read.

While shrimp and grits might seem purely Southern, it also has connections to French colonists who briefly settled here in the 1560s—and, more importantly, to their trade with the Timucua, the powerful Indigenous nation that controlled the region.

Power, Strategy, and Survival

At Fort Caroline (named for King Charles IX, Carolus in Latin), historical plaques claim that the Timucua wanted to be allies with the French. But with 200,000–300,000 Timucua—about the size of Paris at the time—versus only 200–300 French settlers, “allies” seems like a stretch. You see signs and stories like this all over the place.

More likely, the Timucua saw the French as potential trade partners or useful pawns in navigating new trade dynamics between European newcomers and their own local rivals. Pekka Hamalainen is one of my favorite authors about the existing civilizations of North America.

Many accounts of North American history overlook the political complexity of Indigenous societies, reducing them to passive participants rather than active strategists in their own countries. The natives had their own politics to deal with and they saw little threat from a few French exiles.

At this time, the whole "guns, germs, and steel" argument wasn’t as relevant as it would later become. Germs were having an impact, but when it came to weapons, a skilled Timucua soldier with a bow and arrow could easily outmatch a European soldier with a match-lit arquebus—like the one in their museum. Slow to reload, inaccurate, and with limited range, the arquebus was no match for a well-placed Timucua arrow fired from a distance.

European weapons wouldn’t match a skilled archer for centuries to come.

The French Connection

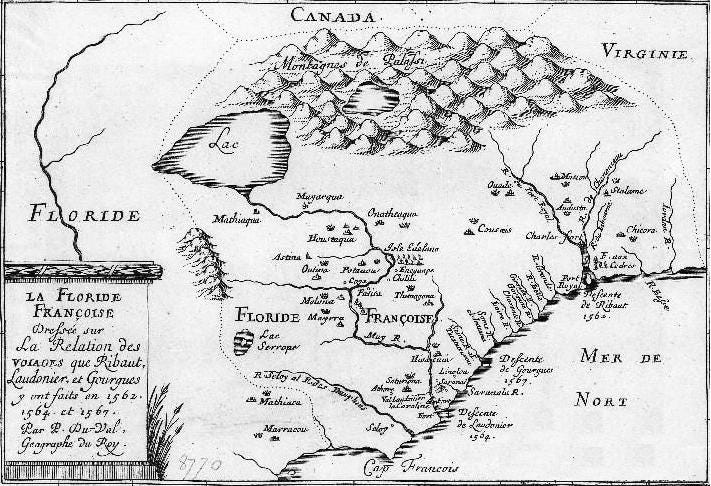

In 1564, French Huguenots (hew-guh-nots in the American pronunciation) fleeing religious persecution in France landed near modern-day Jacksonville and established Fort Caroline on a scenic rise overlooking the St. Johns River.

The St. Johns River, one of the few in North America that flows north, stretches 310 miles (500 km) and could have been a crucial link to the Atlantic and Timucua trade networks—had the colony survived.

The Huguenots never had a chance to establish a lasting foothold. A year after Fort Caroline was built, Spanish forces attacked and wiped out the settlement, ending France’s first major attempt at colonization in North America.

This was in the early days of the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598), culminating in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572), where thousands of Huguenots were slaughtered in a coordinated attack. This civil war is considered one the deadliest in European history.

France in the 16th century was far from the centralized nation we recognize today. It was a patchwork of regional identities, dialects, and allegiances, with places like Nantes, La Rochelle, and Provence feeling as distinct from each other as they did from neighboring countries.

The idea of a unified "French" identity was still developing, at best.

Shrimp, Grits, and Transatlantic Traditions

Long before European explorers arrived, corn had already reached Florida through Indigenous trade networks.

The Timucua and Apalachee used maize in sofkee, a porridge similar to polenta or African pap (mieliepap, ugali, sadza), a connection many people here would have known - one of the area's major historical sites is a former plantation that has only recently begun to acknowledge its more complex history and the lives of the people before their enslavement.

Beyond the first peoples’ crops, Africans forcibly brought to Florida carried agricultural knowledge and culinary traditions that shaped the region’s cuisine. These influences—Indigenous, African, and later European—merged to form the foundation of Southern cuisine and soul food.

Like the “allies” comments at museums, European influence on Southern food is often overstated, while the essential contributions of Indigenous and African cooking techniques, ingredients, and traditions are still being fully recognized.

West Africa adopted maize via the Columbian Exchange, replacing sorghum and millet. Some theories even suggest pre-Columbian transatlantic trade may have brought corn to Africa before Columbus, which I find fascinating - and likely.

Shrimp is abundant near Jacksonville - the Huguenots adapted their fishing skills to Florida’s waters with nets made from local materials, with likely advice from the locals. Shrimp was cooked simply, paired with foraged herbs like sorrel, much as it was in France.

Shrimp and Grits Recipe

Grits are much easy to find in the US. In France, swap grits for polenta (chunkier is better), top with fresh shrimp or langoustines, and dress it up with leeks, asparagus, or lardons. Whether in the American South or the French countryside, the principle remains the same—simple, nourishing food from local ingredients.

note: I’ve written this for shopping in France.

Ingredients (Serves 4):

500g polenta or semoule de maïs

400g shrimp or langoustines, peeled and deveined

2 shallots, finely diced

150ml white wine

200g unsalted butter, cubed and chilled

2 garlic cloves, minced

Optional: leeks, asparagus, or lardons for garnish

Instructions:

Cook polenta or semoule de maïs per package instructions, adding butter or cream (or both). Keep warm.

In a pan, sauté shallots in a splash of white wine until softened. Reduce, whisking in chilled butter to create a smooth beurre blanc.

Separately, cook shrimp in butter and garlic until pink and tender.

Spoon the polenta onto plates, top with the shrimp, and drizzle generously with beurre blanc. Garnish with sautéed vegetables or smoky additions like lardons. Leeks make an excellent companion, and a sprinkle of fresh herbs and a squeeze of lemon brightens everything up.

I am heading back to Turkey from Florida and found this article very serendipitous. I was giving a book tour on a memoir about my father. We used to hunt Timucuan arrowheads on Lake Santa Fe near Jacksonville and his own version of shrimp and grits was a cherished memory of my time with him

I was going to ask if one can find grits in France. I guess not quite?