Notes from the live session! A short reading, some thoughts, and a little space to sit with a story I’ve come back to many times: Graffiti, by Julio Cortázar. It’s not a famous story – or at least not anymore. I’ve had a hard time finding it in print, at least in English - but there’s a link to an archived copy below.

This is likely the part that could potentially cause some legal issues, but I would like to emphasize that this is for literary commentary and/or criticism, LawyerBots of the Internet.

TL;DR

This one goes a bit all over the map — from Paris where Cortázar wrote in Spanish about Argentina, or anywhere really, to Broadway glamorizing the Perón era while the Dirty War disappeared thousands, connecting France's tradition of literary exile (Baldwin, Lost Generation, Cortázar) to chalk drawings that speak when voices are silenced.

Writers in Exile, Writers in Between

I’m starting a series on stories from migrants and exiles in France.

France has long drawn writers who couldn’t stay where they were—Baldwin, Cortázar, the Lost Generation, and many others. Some fled. Some wandered. All wrote from in-between places - between languages, loyalties, and homes.

Cortázar wrote in Spanish, from Paris, for readers in a country that once banned his work.

Writing in exile means making sense of silence—and still speaking.

Julio Cortázar’s Graffiti

Graffiti is set in an unnamed city under tight control about two strangers who begin leaving chalk drawings on the same wall. They never meet. They never speak. But over time, their marks begin to respond to each other—first playfully, then desperately.

It’s about surveillance and silence.

But also about connection.

Presence. Knowing another is present.

“I’m not saying history repeats. But it does start to sound familiar.”

Why Cortázar—and why France?

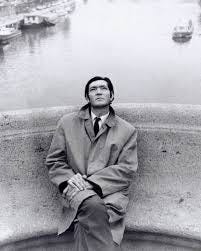

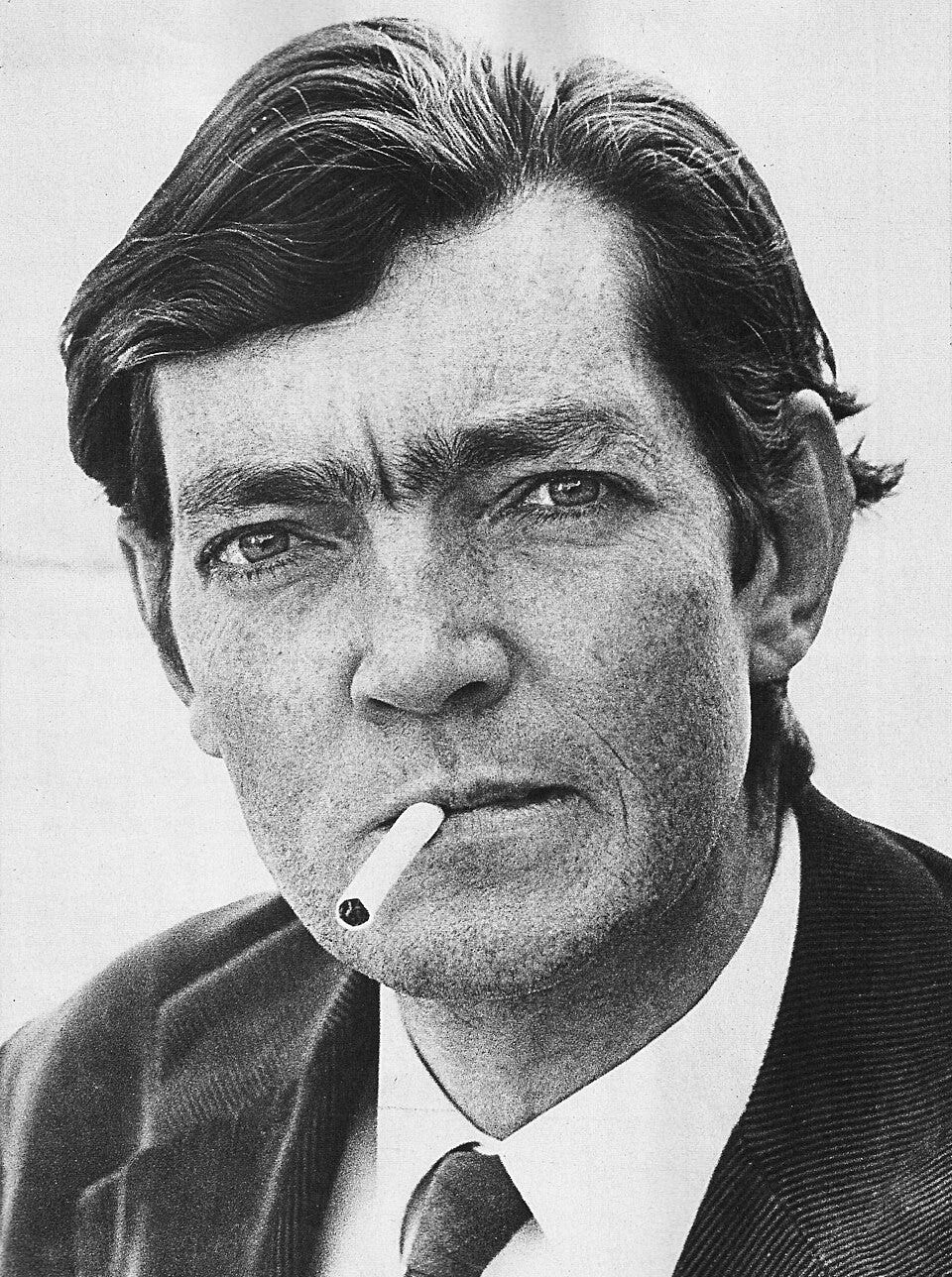

Cortázar left Argentina in the early 1950s and moved to France, where he lived the rest of his life. Not quite exile at first—but at a distance. Space.

Paris offered him room to breathe and bend language. He translated Edgar Allen Poe. He wrote stories that looped, slipped, rearranged themselves. Some were playful, others brutal.

Most refused tidy endings.

Cortázar’s style—structurally experimental, often surreal—don’t line up neatly with today’s literary trends.

He loved ambiguity (which seems deeply unpopular these days), time loops, stories that resisted clean interpretation.

None of that is algorithm-friendly.

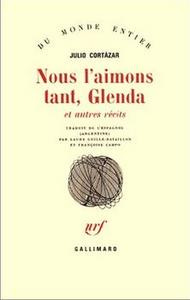

By the 1970s, Argentina had slid into dictatorship. The junta made art and speech dangerous. From France, Cortázar supported resistance efforts and spoke out. Graffiti, published in 1982 in Queremos tanto a Glenda, never mentions the government—or the “Dirty War,” a term coined later by international media.

It doesn’t need to.

Populism & Performance

Cortázar left Argentina long before the junta overthrew Isabel Perón in 1976—but repression was already in motion. Her version of orthodox Peronism was authoritarian, and the military simply scaled it up.

They dropped the populist gloss and made dissent disappear—literally.

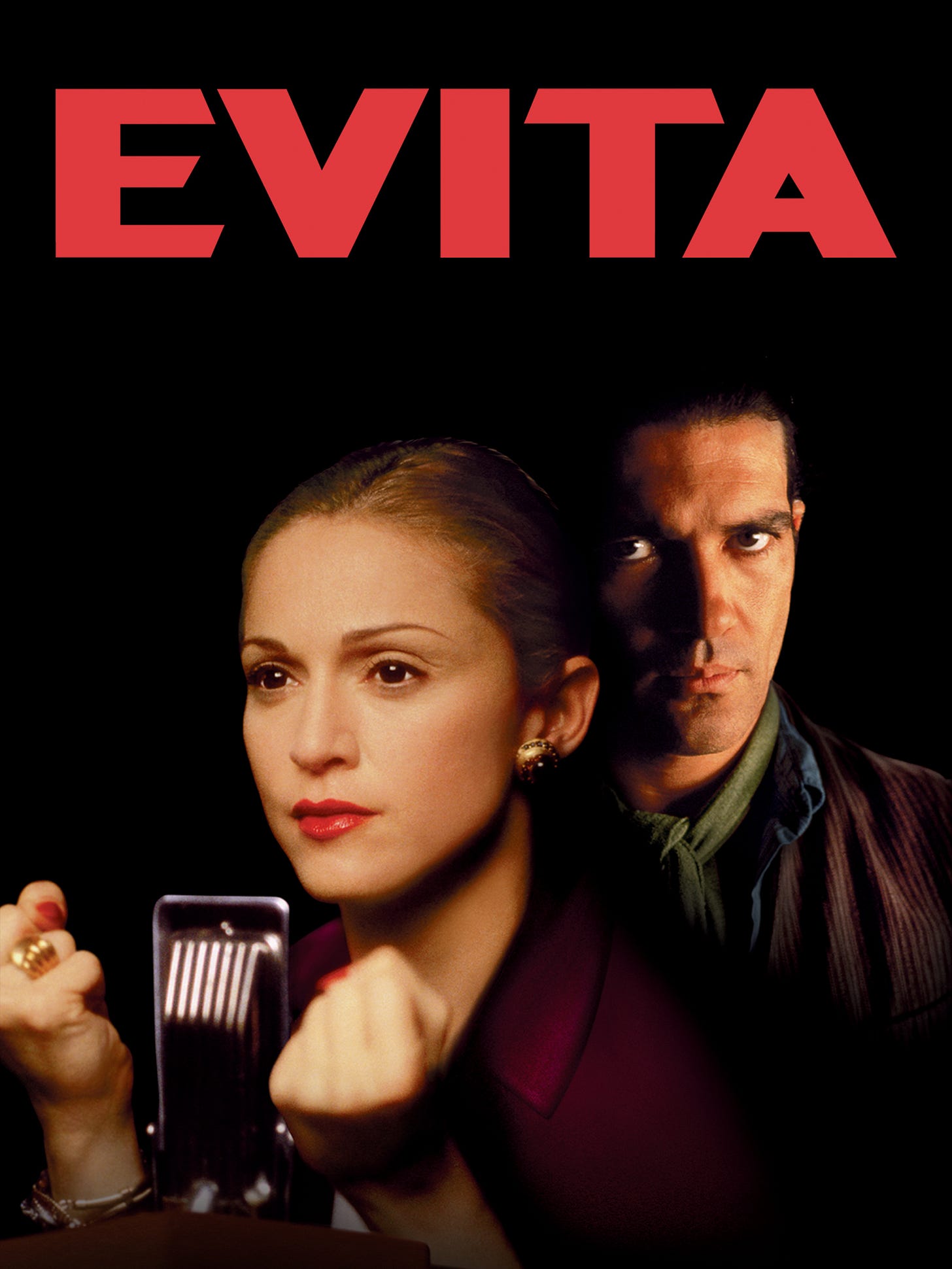

Meanwhile, Evita hit Broadway in 1978, two years into the dictatorship.

Its glittering spectacle rewrote the Perón years in song, turning global attention away from what was really happening: silence, fear, and thousands vanishing. It didn’t name the violence. It didn’t have to. The show became a smokescreen, just when the world needed clarity.

When power outweighs principle, the far left and far right start to look a lot alike. Who cares what they call themselves if they’re throwing you into the back of a van?

Don’t Cry for Me Argentina Patti LuPone (1980)

LuPone performed this live 8 times a week when Evita was on Broadway, not including additional appearances on shows like Merv Griffin. Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice had previously collaborated on Jesus Christ Superstar. The musical was based on the life of Eva Perón and premiered in London's West End in 1978 before moving to Broadway.

Evita hit Broadway in 1978, two years into Argentina's military dictatorship, creating this surreal situation where international audiences were enjoying a glamorous musical about Argentine populism while the actual country was in the midst of state terror and disappearances.

Second-person and soft resistance

What makes Graffiti linger isn’t the plot—it’s the form. The second-person voice wraps around you: “you draw,” “you wait,” “you almost laugh.” It’s intimate without ever being confessional. It pulls you in.

What I keep returning to is how an act—unlabeled, unclaimed, maybe unnoticed—still means something.

“You drew a fast landscape… a mess of random lines. But she would know.”

There’s tenderness. Not defiance, exactly. Not resistance in capital letters. Just the quiet insistence that someone else might understand.

Legal gray zones

I probably shouldn’t have read this story aloud.

Cortázar died in 1984, which means his work won’t enter the public domain in France or the U.S. for decades. But Graffiti, as I mentioned, isn’t easy to find—there’s a Spanish version floating around online (published in Queremos tanto a Glenda - see below), but English are trickier to locate.

And reading it aloud in 2025, to a small group of people sitting in a different country, felt like a good story at a good time for that story.

We’re not from here either

If you came, thank you. If you didn’t, here’s the takeaway: stories like this aren’t meant to be decoded. They’re meant to stay with you in weird, low-volume ways.

A drawing. A line.

“She would know.”

I love how Cortazar does so much with so few words.

Is this even a good idea?

What’s the smallest act you’ve done lately that felt like it mattered?

Share this if it speaks to you.

The next reading is coming soon.

Please let me know!

I’d love to hear about your own favorite stories, what connect for you, what stays in your mind no matter what else is going on in the world.

Appendix:

texts used in this piece

The Full Text of Cortazar’s “Graffiti”

An English version I was working from. I made my own edits. I’ll forward them along in a while.

The complete text of We Love Glenda So Much - a personal favorite of odd stories, stylistically very different than Graffiti.

The original text in Spanish

Eduardo Galeano’s Days & Nights of Love & War

I mention this in my reading. While this is one of Galeano’s more emotionally difficult books to read, he’s written many others that are, in my opinion, just as profound and often more beautiful.

Here’s the full text

https://archive.org/details/daysnightsoflove00gale/mode/2up

The population becomes the internal enemy. Any sign of life, of protest, or even mere doubt, is a dangerous challenge… Apart from breathing, any human activity can constitute a crime.”

— Days and Nights of Love and War

.

Share this post